Part Two: Channels of Grace

Penance

As Catholics, we have no doubt that Christ instituted the

sacrament of Penance on Easter Sunday night. St. John describes the event in

great detail.

As Catholics, we have no doubt that Christ instituted the

sacrament of Penance on Easter Sunday night. St. John describes the event in

great detail.

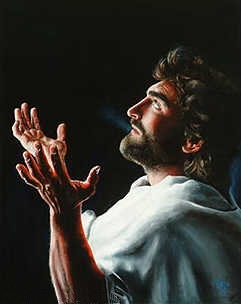

In the evening of that same day, the first day of the week, the doors were closed in the room where the disciples were for fear of the Jews. Jesus came and stood among them. He said to them, “Peace be with you,” and showed them His hands and His side. The disciples were filled with joy when they saw the Lord and He said to them again, “Peace be with you. As the Father sent me, so I am sending you.” After saying this He breathed on them and said, “Receive the Holy Spirit. For those whose sins you forgive, they are forgiven, for those whose sins you retain, they are retained” (John 20:19-23). As we examine this narrative in the gospels, we notice a number of striking features. It was Christ’s first appearance to the assembled disciples since His resurrection from the dead. To quiet their fears, Jesus told the frightened apostles, “Peace be with you.” In doing this, He gave what He was about to institute its first name, the sacrament of peace. It was to reconcile a sinner and therefore restore peace between man and an offended God. Its effect was also to remove guilt from a sinful soul and therefore give peace within a man’s heart. Why? Because the most fundamental cause of all disturbance of soul and the absence of peace is the sense of guilt. The final effect of this sacrament was to restore harmony in a society injured or destroyed by enmity, greed, and injustice, and therefore produce peace between people in the community in which they live. Moreover, Jesus told the apostles He was sending them as the Father had sent Him. The Father had sent the Son as the merciful Savior of sinners. In fact, that is what the name Jesus means, “the One who saves.” Saves from sin. In like manner, the apostles and their successors, the bishops and priests of the Catholic church, are being sent among sinful people as ministers of God’s mercy to bring them the threefold peace which is lost by sin. As Christ spoke to the apostles, He breathed on them and said, “Receive the Holy Spirit.” It is by divine power that priests are empowered to forgive sins. Even as sin estranges a soul from God, so its forgiveness restores the soul’s friendship with God which is holiness.

Teaching of the ChurchIn the course of her history, the Catholic Church has many times been required to defend and explain her faith in the sacrament of Penance. However, as with so many other revealed truths, the most elaborate doctrinal exposition of the sacrament of Penance was made by the Council of Trent. Its principal defined dogmas cover every aspect of this sacrament of God’s mercy.

Confession of Sins

Typical of the Church’s tradition are the liturgical texts for the ordination of bishops. One formula of episcopal ordination dating from the latter half of the fourth century, offers this prayer to God. Grant him O Lord Almighty, by Thy Christ, the fullness of Thy Spirit, that he may have the power to pardon sin, in accordance with Thy command, that he may loose every bond which binds the sinner by reason of that power which Thou hast granted to Thy apostles (Apostolic Constitutions, 8,5,7). Equally typical was the Church’s belief that in order to obtain remission of sins, a person had to confess to the bishop or priest. In the mid-fifth century, an abuse had crept in which took papal intervention to stop. Pope Leo I, writing to a group of bishops in Italy, says: I have recently learned that some are presuming to act against a rule set down from apostolic times. I decree that the practice they have brazenly introduced be completely stopped. I refer to the fact that penitents are told they must publicly recite each one of their sins, which they had previously set down in writing. It is sufficient that the sins which burden a person’s conscience should be secretly confessed only to priests (Letter to the Bishops of Campania, 168,2). Confession of sins was therefore presumed. The pope was simply correcting a rigorist interpretation of what he called an apostolic practice, namely the private confession of one’s sins to a priest. By early fifteenth century, partly due to the lax morality of some of the clergy, the idea arose that an immoral priest or bishop could not give absolution. In fact, a general council of the Church had to be called to decide that internal sorrow for sin was not sufficient to be reconciled with God. Moreover, the council declared “in order to be saved, a Christian has the obligation, over and above heartfelt contrition, of confessing to a priest when a qualified one is available, and only to a priest, not to lay person or persons, no matter how good and devout the latter may be” (Council of Constance, February 22, 1418). A century later the Council of Trent defined in great detail, as we have seen, the necessity of what has come to be called auricular confession of sins in the sacrament of Penance. The new Code of Canon Law restates this doctrine in clear terms. Individual and integral confession and absolution constitute the sole ordinary means by which a member of the faithful who is conscious of grave sin is reconciled with God and with the Church (Canon 960). Since the first Code of Canon Law was published in 1917, questions had been raised about the validity of general absolution. On several occasions, the Holy See had been asked under what conditions sacramental absolution could be given to many at the same time. The cases applied to situations where there was either no priest or a priest could not stay long enough to hear the confessions of all the penitents. Such too would be the case of absolving soldiers when a battle was imminent or in progress. The same would hold true for civilians and soldiers in danger of death during a hostile invasion. Rome’s decisions on such cases prompted the provision in the new Code of Canon Law which states that, “General absolution, without prior individual confession cannot be given to a number of penitents together unless:

There is one more condition which the Church sets down for valid general absolution. “For a member of Christ’s faithful,” says the Code, “to benefit validly from a sacramental absolution given to a number of people simultaneously, it is required not only that he or she be properly disposed, but be also at the same time personally resolved to confess in due time each of the grave sins which cannot for the moment be thus confessed” (Canon 962). Accordingly, Christ’s precept of making a personal confession of mortal sins remains even when for exceptional reasons, general absolution had been received. The Code of Canon Law also repeats what by now is a centuries-old prescription regarding first confession. It occurs in conjunction with the precept on first Holy Communion. It is primarily the duty of priests and of those who take their place, as it is the duty of the parish priest, to ensure that children who have reached the use of reason are properly prepared and, having made their sacramental confession, are nourished by this divine food as soon as possible (Canon 914). Absolutely speaking, by divine law, the sacrament of Penance must be received before a person in mortal sin may receive Holy Communion. By ecclesiastical law, “All the faithful who have reached the age of discretion are bound faithfully to confess their grave sins at least once a year” (Canon 989). However, “the faithful are recommended to confess also their venial sins” (Canon 988). In fact, one of the true developments of doctrine in modern times has been the growing realization of the great value of frequent confession, even when no mortal sins are to be confessed. It is true that venial sins can be forgiven in other ways, but frequent sacramental confession has values that have been proved by long experience. By it genuine self-knowledge is increased, Christian humility grows, bad habits are corrected, spiritual neglect and tepidity are resisted, the conscience is purified, the will strengthened, a voluntary self-control is attained, and grace is increased in virtue of the sacrament itself (Pope Pius XII, The Mystical Body of Christ, 88). Those who have cultivated the habit of receiving the sacrament of Penance often, on a regular basis, testify to the truth of this teaching of the Church. It is all the more necessary in a world that has become so oblivious of the evil of offending an all-loving God.  Copyright © 2002 Inter Mirifica

Pocket Catholic Catechism |

It may be surprising that Christ’s institution of the sacrament

of Penance was not seriously challenged until the late Middle Ages.

It may be surprising that Christ’s institution of the sacrament

of Penance was not seriously challenged until the late Middle Ages.